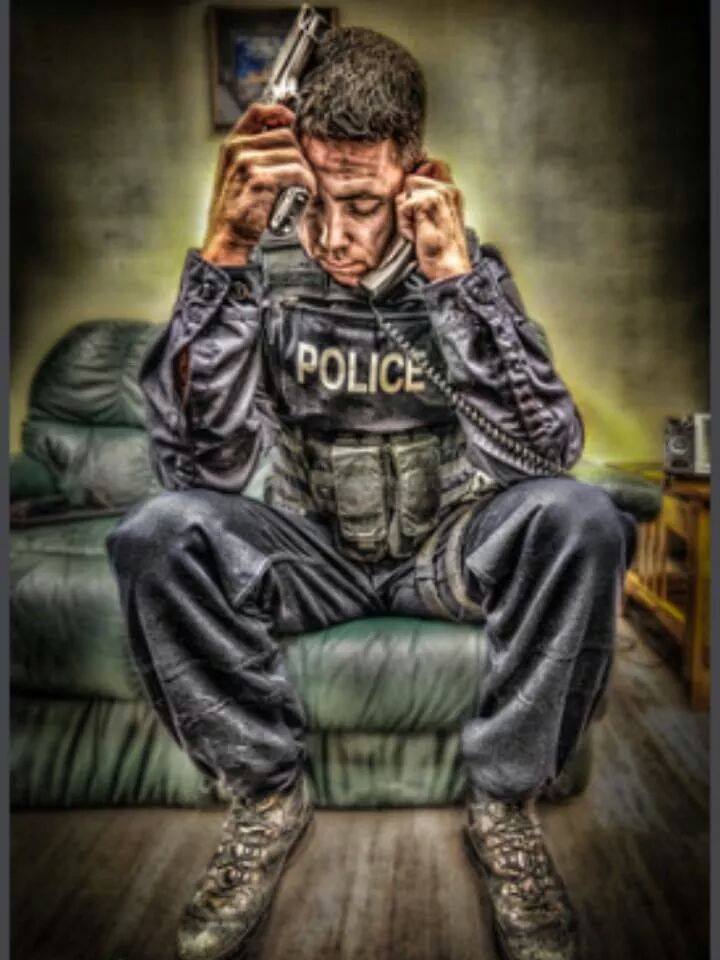

Police officers in New Jersey are 30 percent more likely to commit suicide than the general population — and the numbers appear to be getting worse despite state programs designed to help officers.

The troubling police suicide statistics are back under the spotlight after news Tuesday that the Sayreville police officer who had been found shot dead Monday morning had killed himself.

Det. Matt Kurtz, 34, had been on the force for nine years and was honored last year for helping to rescue an an 83-year-old man from a house fire. He was married with two children. He and his wife purchased their home in Sayreville in 2012.

19 cop suicides in 2015

Kurtz became the sixth police officer to take his own life just this year, according to the New Jersey State Policemen’s Benevolent Association.

Last year, officials at the police union counted 19 suicides.

That’s a significant number, considering that a 2009 report from a police-suicide state task force had counted 55 suicides by active and retired law enforcement officials between 2003 and 2007 — an average of 11 suicides a year at that point.

“We’re supposed to be pillars of strength and when we falter or make a mistake it’s often very difficult for us to recover emotionally.”

“We’re trying to do everything we can,” the state’s PBA union president Pat Colligan said Wednesday. “It’s frustrating that these officers aren’t reaching out and getting the help that we’re offering them.”

Sayreville Police Chief John Zebrowski, in announcing the news Tuesday afternoon about the suicide, addressed the menace of suicide among the men and women in blue.

“Matthew’s death sheds more light on an insidious predator that has taken his life and so many others in law enforcement as well,” he said. “Sadly, suicide remains a leading cause of police officer deaths.”

‘People have lost respect’

Among the reasons for heightened risk is the unique job-related stress that police and corrections officers face.

“It’s not pulling the gun that adds to stress, it’s doing CPR on an infant or showing up at a suicide where the kid, their son or daughter found them.”

Police also have greater access to firearms, which makes suicide that much easier to accomplish.

“We’re supposed to be pillars of strength and when we falter or make a mistake it’s often very difficult for us to recover emotionally,” said Denville Police Chief Christopher Wagner, president of the New Jersey State Association of Police Chiefs.

Colligan said even an officer in a small town, who may never have to fire his gun, deals with tremendous stress

“It’s not pulling the gun that adds to stress, it’s doing CPR on an infant or showing up at a suicide where their son or daughter found them. That’s the stuff that grates on us.”

Like anyone else, police also struggle with mental illness, particularly depression and bipolar disorder, as well as problems with relationships, finances and health, which can trigger suicidal thoughts.

“People call us when they’re down and out, in the worst times of their lives, and some police officers see that over and over, day in and day out, and it weighs on us,” Wagner said.

And Colligan said what police read and see in the media can hurt as well.

“Our profession has taken a strong hit in the last 2 to 3 years. We were always held on a pedestal and now we’re almost vilified on traffic stops now,” he said. “People have lost respect for police officers and that’s a tough thing to handle too.”

Why cops don’t ask for help

Police and corrections officers are more likely not to seek help, the 2009 state task force found, thanks to “a law enforcement culture that emphasizes strength and control.”

Police and corrections officers are more likely not to seek help, the 2009 state task force found, thanks to “a law enforcement culture that emphasizes strength and control.”

Among the reasons police may not seek help:

- Perceptions and distrust of mental health providers

- Stigma associated with seeking help

- Worries about loss of privacy that may adversely affect their careers

- Embarrassment or shame.

- Feeling comfortable with counselors who do not have law enforcement experience.

- Worries about losing their weapon, job and health benefits.

But police officers looking for help have several options.

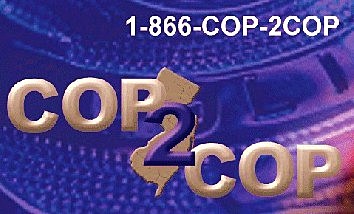

New Jersey’s nationally recognized Cop 2 Cop crisis intervention hotline has offered police confidential peer counseling sine 1998. The hotline is staffed 24 hours every day by volunteer retired law enforcement personnel and mental health professionals.

The New Jersey Critical Incident Stress Management Team (NJCISM) and the New Jersey Crisis Intervention Response Network (CIRN) also offer a hotline and counseling to emergency responders.

Wagner says departments are “aware of the signs and symptoms and we will mandate where necessary that a police officer go and speak with somebody.”

He says a Cop 2 Cop poster “should be hanging in every police department, every headquarters and every barracks and every station,” but some officers may not pick up the phone.

“Unfortunately, our work is ongoing and we haven’t gotten to everybody yet,” Wagner said